Ten years ago this week, I was invited to attend a planning meeting in Stirling. The agenda was how to develop academic leaders in Scotland’s universities. I had some experience of the topic, having worked with my own colleagues on this for some years. At that time in my university, the terms “leadership” and “management” were used by us with caution, they were deemed inappropriate to the context by many, even rejected as offensive by a few. Nevertheless, those with the purse strings and the influence over policy deemed it good for universities that they should develop leadership capacity. It would make them more consistent and resilient, more efficient, perhaps. It was an unarguable challenge that better leadership and management of people must be a good thing. How best to do it was the issue we were discussing.

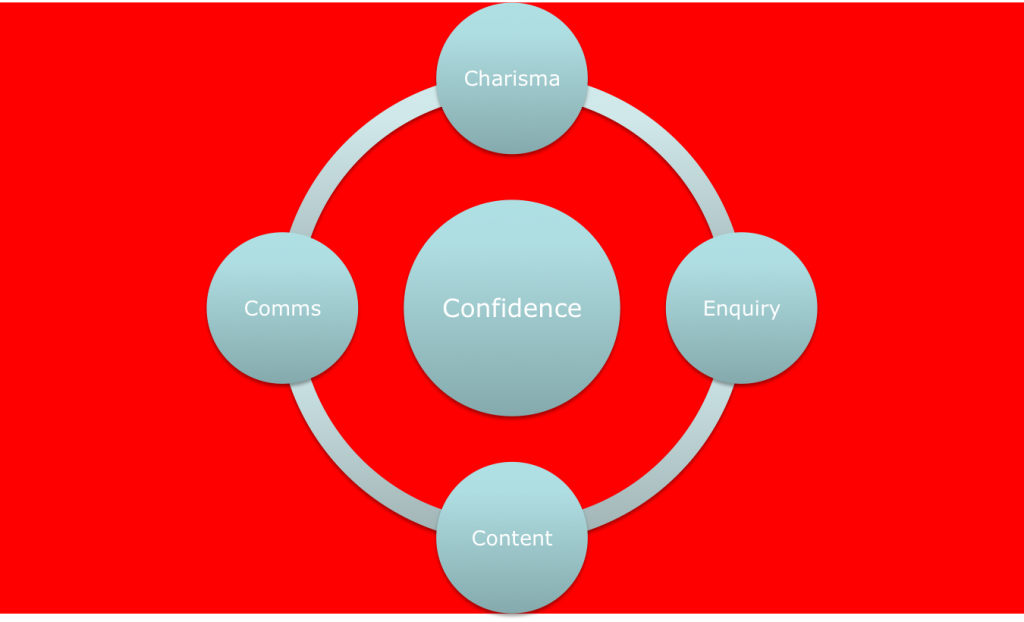

Not for the first time in my career, I drew a picture of what might be possible; a crude diagram of a process to develop leadership. A couple of long-standing colleagues had the courtesy to ask me to talk them through it. By the end of the meeting I had been offered a sum of money and a short space of time to go and work up the idea.

I had already decided to move on. I had a job offer from another university. However, this meeting opened my mind to the idea that it might be possible to do something at the systemic level; for the sector, rather than just repeat the experience of developing a single organisation from within. As there was no obvious structure from which to do this kind of work, I turned down the other job and went freelance, just like that. For someone who had spent the previous 20 years in organisations that offered monthly salary, pension, holidays, sick pay, company and relative security, this felt like jumping off a very high cliff with just a business card in my hand.

My first client was the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education, itself a very new organisation formed from the best of a lot of other efforts distributed around the Higher Education sector. I became an associate on 1st December 2005 and have been one ever since. Other clients followed. In ten years, Workhouse8 has propagated itself entirely by word of mouth and taken me to all corners of the UK and occasionally beyond.

The first “product” was a leadership programme for Scottish Heads of Department; we ran 10 cohorts of that before it was re-designed as a UK-wide offering. Leadership programmes remain a core part of the work but they have spawned or have been complemented by other work on governance, process review, trouble-shooting, organisational development, big systemic collaborations, critical friendship and coaching. Higher Education remains a big part of the landscape, but I have also worked extensively in Health, Social Care, Government, the creative sector and other types of organisations.

I feel a strong sense of privilege to be doing this kind of work. I am entrusted with the deeper concerns and inspirations of individuals, teams and sometimes whole organisations. Taken together, they give me a wide and deep view of a system at work, a rich and constantly changing complexity of autonomous organisations, public bodies, political pressures, resourceful behaviours, wild successes and traumatic blockages.

It is not possible to make complete sense of complex organisations; to claim such a thing would be arrogant and prescriptive and wrong. It is possible (and necessary) to work with people within complex organisations to help them make sense of what they can influence and to do so knowingly and respectfully.

The work is endlessly fascinating, but that is not, in itself, the reason for doing it. It is work that must have outcomes. Frustratingly, these outcomes are often not known in advance, nor wholly visible during or after an intervention. When positive changes do manifest, it is not always easy nor honest to attribute them wholly to a narrow intervention. OD is not a controlled laboratory environment. It is conducted in vivo, in the field, in real time, in the middle of chaos.

I never work alone; I work with the clients, I partner with other OD and learning specialists in the field and within organisations. The use of “we” on the Workhouse8 website is conscious and deliberate; not a “royal we”, but a collaborative “we”, an engaged “we”.

I would like to thank all those who have participated in the first ten years of this escapade; the fellow consultants, the senior managers, the HR & OD teams, the participants, the coachees, the practical support (whose patience I know I test regularly), the critics (especially the ones who have been bold enough to speak out directly), the doubters and the enthusiasts.

I would like to thank those to whom I have turned for support: the supervisors, the course tutors, the critical friends, the quiet voices. The learning has been wondrous.

and the next ten years? Well, that is a whole new adventure.